1.

Cristoforo Colombo,

1451-1506.

Epistola Christofori Colom . . .

Rome: Stephan Plannck,

1493.

Lilly Library call number:

E116.1 1493 Vault

2.

Cristoforo Colombo,

1451-1506.

Epistola Christofori Colom: cui etas nostra multum debet: de

insulis Indie supra Gangem nuper inventis.

Rome: Stephan Plannck, 1493.

Lilly Library call number:

E116.1 1493a Vault

Fernando and Isabel made sure that Columbus's First Letter from America

would be widely distributed and read throughout Europe. Probably at

their initiative, the book went through nine editions within

a year: three editions in Rome, one in Antwerp, one in Basel, three in

Paris, and another in Basel in 1494. An Italian translation in poetry by

Giuliano Dati had three editions in 1493 (one in Rome and two in

Florence). A German edition appeared in Strassburg in 1497. A second

edition in Castilian appeared in Valladolid in 1497.

This copy of the second Plannck edition in Rome is open to the final

page, which describes Columbus as "Christopher Columbus, Commander of

the Ocean Fleet."

3.

Bernardino Carvajal, 1456-1523.

Oratio super praestanda solenni obedientia sanctissimo . . .

Alexandro papae VI. . . Rome:

Stephan Plannck, 1493?

Lilly Library call number:

DP161.5 C3 Vault

In a further effort to assure Castilian sovereignty over the newly

discovered islands, Fernando and Isabel appealed to the

fifteenth-century's equivalent of an international arbiter, Pope

Alexander VI. Their ambassador to the papacy, Bernardino Carvajal, made

this speech to the pope on June 19, 1493, in which he presented

Castile's claims and requested that Alexander confirm Castilian

possession of the islands.

The appeal was successful. Alexander issued a papal decree, Inter

caetera, confirming Castilian possession of the islands that Columbus

had discovered and any other islands or continent that Castilians might

discover in the future beyond an imaginary line in the Atlantic Ocean.

This Line of Demarcation, according to Inter caetera, was drawn from the

Arctic or North Pole to the Antarctic or South Pole, one hundred leagues

south and west of the Azores and Cape Verde Islands.

Spanish appeal to the papacy had the intended effect. Portugal, worried

that the papal decrees gave Castile a right to the eastward route to the

Indies and to lands off the West African coast, agreed to negotiate

directly with the Spanish monarchs. On June 7, 1497, Castile and

Portugal signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, setting the Line of

Demarcation 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Through this

compromise, Castile secured possession of Columbus's discoveries,

including eventually North and South America, while Portugal retained

rights to lands discovered east of this line, which included sub-Saharan

Africa and the East Indies, to which, one month later, the Portuguese

king would despatch Vasco da Gama.

4.

Carlo Verardi, 1440-1500.

In laudem serenissimi Ferdinand hispaniane regis Bethicae

& regni Granatae obsidio victoria & Triu[m]phus. Et

de insulis in mari Indico nuper

inuentis. Basel: Johann Bergmann

de Olpe, 1494

Lilly Library call number:

PA8585.V39 H57 1494 Vault

5.

Cristoforo Colombo, 1451-1506.

Eyn schön hübsch lesen von etlichen insslen die do in kurtzen

zyten funden synd durch de künig von hispania . . .

Strasbourg:

Bartholomäus Kistler, 1497.

Lilly Library call number:

E116.1 .G4 1497 Vault

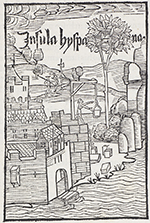

This is the first German edition of the First Letter from America.

Typical of German printed books, it bears a beautiful woodcut

illustration on the frontispiece. It is the first printed work to

introduce a religious motif in the American story; Christ addresses King

Fernando and his courtiers.

Spanish publishers knew that the Columbus voyage was a Castilian

enterprise, and that Queen Isabel of Castile was the ruler of the new

islands. But publishers in other parts of Europe could not seem to

understand that Columbus reported principally to the queen, not the

king.

6.

Fernando V,

1452-1516, and

Isabel I,

1451-1504.

Libro en q[ue] esta[n] copiladas algunas bullas de n[uest]ro muy

s[an]cto padre co[n]cedidas en fauor de la iurisdicio[n] real de sus

altezas, & todas las pragmaticas q[ue] esta[n] fechas para

la buena governacion reyno. Alcalá de

Henares: Lançalao Polono,

16 November 1503.

Lilly Library call number:

DP161.5 S73 Vault

Having acquired formal recognition of Castilian sovereignty over La

Española, Fernando and Isabel authorized colonization of the

island. A colony would constitute effective occupation—one of

the most important proofs of sovereignty. Events on La Española from

1493 through 1497, however, punctured the euphoria with which Spanish

colonists had volunteered for the second voyage. The fleet made a fast

safe crossing, but found the thirty-nine men left behind in La Navidad

had been killed either by disease or by the local Indians. The natives

that Columbus had described as meek and gentle in the First Letter from

America turned out to be hostile and dangerous.

The environment also proved dangerous. More than three hundred Europeans

became seriously ill after they went ashore, including Columbus, and

many died. Columbus diverted his energies into conquering the Indians

and exploring further west, where he still expected to find the Asian

continent. He left the administration of the colony in the hands of his

brothers Bartolomé and Diego Colón, who had just arrived from France and

Italy, never having lived in Spain.

The Spaniards who had come to colonize the island became dissatisfied

with the Columbus brothers' authoritarian and uninformed rule. Groups of

colonists moved away from Columbus's headquarters city of La Isabela to

form squatter settlements, but the Columbus brothers attacked them and

arrested them as rebels. The colonists felt that the denial of their

rights as Spanish citizens had become intolerable. The appellate judge

Columbus had appointed for the whole island, Francisco Roldán, led a

revolt in which almost one hundred colonists moved to the Xaraguá

Peninsula and established a new town. Most of the other colonists simply

gave up; they returned to Spain on the four resupply fleets that crossed

between Spain and Española. The number of colonists remaining on the

island fell below three hundred.

As all of this bad news trickled back with the returning fleets, the

reputation of Columbus's colony deteriorated. When Columbus returned to

Spain in 1497 and started organizing his third voyage, he could not

recruit enough Spaniards to man his ships or settle his colonies.

In desperation, he asked the monarchs for permission to recruit condemned

murderers, who would gain commutation of their death sentences after ten

years of unpaid labor in the colonies. This royal provision of 1497, as

well as the 1493 papal decrees establishing the Line of Demarcation,

were quickly incorporated into books of Castilian laws such as this one.

The book is open to the royal permission for Columbus to recruit

convicts. The text notes that this decree was announced by the public

crier of the city of Granada, who read it aloud in the city's principal

marketplace on October 14, 1497. Despite the inducement offered,

Columbus was able to recruit only ten convicts, six of them Gypsies

convicted of murder.

Columbus's third voyage was the first to carry European women to America.

We know the names and identities of only four of these pioneer women:

Catalina de Sevilla was accompanying her husband, noncommissioned

officer Pedro de Salamanca; Gracia de Segovia appears to have been

single and traveling alone; Catalina de Egipcio and María de Egipcio

were Gypsy women convicted of murder who took advantage of the offer of

commutation of sentence after ten years of unpaid service in the

Americas.

7.

Amerigo Vespucci, 1454-1512.

Alberic' vespucci' laure[n]tio petri francisci de medicis salutem

plurima[m] dicit. Paris:

Félix Baligaut and Jean Lambert, 1503.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V5 1503

Vault

Columbus explored the coast of Venezuela in 1498. Realizing from the

volume of water pouring out of the Orinoco River delta that this was a

continent, he informed the monarchs that he had taken possession of this

"Other World" in their name. Fernando and Isabel sent Alonso de Ojeda

and Juan de La Cosa the next year to establish colonies on the mainland

of South America and explore further for a passage to Asia. The

Florentine merchant, Amerigo Vespucci, went on this voyage, probably as

agent of the Sevillian merchants who had invested in the costs of the

voyage.

After he returned to Spain in June 1500, Vespucci sent this letter to

Lorenzo Pier Francesco de' Medici, cousin of Lorenzo de' Medici the

Magnificent, describing the voyage. In Florence, Giovanni Giocondo

translated the letter into Latin.

In this letter, Vespucci claimed that

he had made astronomic observations and measured longitude by a new

method, using the conjunction of the moon with Mars on August 23, 1499,

as his reference. Scholars now doubt that he made observations of lunar

distances off the Venezuelan coast.

8.

Pietro Martire d'Anghiera,

ca. 1457-1526.

Libretto de tutta la nauigatione de re de Spagna de la isole et

terreni nouamente trouati.

Venice:

Albertinus Vercellensis,

1504.

Lilly Library call number:

E141 .A6 1504 Vault

As Spanish fleets continued to explore and map the American coastline,

King Fernando and Queen Isabel drew on every possible resource to

publicize their sovereignty. One of the most effective publicists was an

Italian humanist, Pietro Martire d'Anghiera, who had been a chaplain on

Isabel's staff since 1488. Assigned responsibility for writing the

history of the explorations, d'Anghiera chose to do so in the form of

letters to friends and patrons in Spain and Italy. These letters shaped

European impressions of the Americas.

The popularity of the letters stemmed from a paradox; using the classical

style admired in intellectual circles, they narrated high adventure in

exotic places. D'Anghiera never saw the Americas, though he was

appointed abbot of the island of Jamaica. He acquired his information in

the traditional way of Castilian royal chroniclers, by interviewing the

participants (he was acquainted with Columbus, Cortés, Magellan, Cabot,

and Vespucci), or reading the written reports captains submitted to the

House of Trade in Seville. D'Anghiera shaped these

first-hand accounts into an elegant narrative true to the norms of

classical rhetoric. His first collection of letters, written between

1488 and 1525,

recounts the first three voyages of Columbus. With

d'Anghiera's permission, the letters were translated into the Venetian

dialect by Angelo Trevisan, Venetian ambassador to Spain, with the

translator's description of Columbus at the beginning of the collection.

The Libretto is the earliest known publication of Pietro

Martire d'Anghiera, the first historian of the Americas. It is the first

published collection of his letters; it contains the first account in

printed form of the third voyage and a part of the second voyage of

Columbus. This beautiful copy, another in the John Carter Brown Library,

and a third lacking the title leaf in the Marciana Library in Venice are

the only recorded surviving copies.

The provenance of this copy of the Libretto is faithfully

and charmingly related by Douglas G. Parsonage:

On a certain visit to Budapest in 1929 Lathrop C. Harper called as

usual on his old friend Gustav Ranschburg, antiquarian bookseller.

Civilities were exchanged, companionable gossip started, and then

the inevitable request from Harper: "Let's see some books." I was

not there myself and cannot fill in the details as to what was shown

and rejected, what else was looked at and set aside for further

consideration. But I do know that at a certain point a nondescript,

unimpressive volume in vellum lettered on the spine Opusc.

Var. came to light. It was a volume containing twelve

sixteenth-century pamphlets bound together with a manuscript index,

with such unpromising titles as Conjectura de libris de

imitatione Christi; Dissertatio de Tracala; De numismatis et

nummis antiquis; and others.

Knowing Mr. Harper, I would like to imagine a certain bird-dog

attitude that may suddenly have developed. On the other hand, his

poker face when the stakes were high was notorious. But I only have

his own version of what happened next, and that was a laconic: "I

asked him the price, and said I'd take it." One has to remember that

all the titles were in Latin, of which Mr. Harper had little or no

real knowledge; that the first nine pamphlets could have no possible

interest for Harper or his customers; that the tenth was listed in

the manuscript index as Navigazione alla scoperta

d'America, Venezia, 1504; and the last two were similar to

the first nine. Yet I have Mr. Harper's word, which I know to be

true, that this is the title that caught his eye.

The book itself, under its proper title of Libretto de Tutta

la Nauigatione de Re de Spagna . . . is the first printed

collection of voyages, derived from Peter Martyr and covering the

first three voyages of Columbus. In his voluminous reading Harper

must somewhere have encountered the title and remembered it. No copy

has ever appeared for sale, and it is so rare that few

bibliographers have ever seen it or referred to it, except to

mention its legendary rarity. And here was a second perfect copy,

nestling anonymously in the middle of a dull collection of tracts in

a utilitarian vellum binding lettered Opusc. Var.!

It came to America in Harper's pocket; was separated and placed in a

morocco case, and kept side by side with the parent volume in

Harper's safe until he died. To my knowledge he never offered it for

sale, and indeed few people knew he had it. During the thirties

times were bad, and few libraries or collectors had the kind of money Harper felt it was worth—and

rightly! Came the forties and his slow withdrawal from active

bookselling, partly due to advancing years and partly to family

inheritance matters that occupied most of his time, and at his death

in 1950 it was still in the safe.

With the sale of the business after Harper's death, and the

availability of a typed inventory of the books in his stock, some of

the more knowledgeable dealers tried to buy the business for this

one book. But only one of several collectors who saw the list was as

alert as Harper had been to this outstanding rarity, which was typed

out on a single line without any comment or price with the four or

five thousand other books in the Harper stock. That Bernardo Mendel

was the eventual successful purchaser of the business against

considerable odds is evidence of the knowledge and acumen that went

into forming his own library that now enriches the shelves of the

Lilly Library at Indiana University. This book was a gift of Mr.

Mendel on the occasion of the dedication.

The book is open to Trevisan's description of the personal appearance of

Columbus:

Christopher Columbus, Genoese, a man of tall and imposing stature,

ruddy-complexioned, of great intelligence, and with a long face,

followed the Most Serene Sovereigns of Spain for a long time

wherever they went.

9.

Amerigo Vespucci, 1451-1512.

Mundus Novus. Augsburg:

Johann Otmar, 1504.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V5 1504 Vault

Amerigo Vespucci returned from Ojeda's explorations and was summoned to

Lisbon by King Manuel of Portugal. He left Seville so hastily that he

did not have a chance to say goodbye or gather his belongings. The king,

after receiving news of Pedro Alvares Cabral's accidental landfall on

Brazil (April 23, 1500), ordered follow-up explorations. Probably, King

Manuel, having learned that Amerigo had found a new system for measuring

longitude, wanted him to fix the position of Brazil with respect to the

Line of Demarcation to see whether it was east or west of the line. If

it was west, it would belong not to Portugal but to Spain.

On May 13, 1501, Amerigo sailed with a fleet of ships in the service of

Portugal. They reached the South American coast at Cape Saint Augustine

(8°64'S), went south to latitude 46'S, and returned to Lisbon in July

1502. Amerigo wrote letters to his Florentine patron describing this,

his second and last voyage to the Americas.

The book is open to the title page, where Amerigo calls the Americas "A

New World." In this letter, as in his others, Amerigo gives the false

impression that he commanded or piloted a ship, never mentioning Ojeda

or any other captain.

10.

Amerigo Vespucci, 1451-1512.

Be [i.e. De] ora antarctica per

regem Portugalli pridem inuenta.

Strasbourg: Matthias

Hupfuff, 1505.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V5 1505 Vault

In 1505, the German humanist Matthias Ringmann translated and published

Amerigo Vespucci's second letter to Lorenzo Pier Francesco de' Medici,

in which he described his voyage with the Portuguese to South America.

Ringmann changed its title from New World to About the Antarctic

coast long ago discovered through the king of Portugal.

The book is open to an illustration that purports to show Brazilian

natives. This picture had a powerful influence on Europe's image of

native Americans. In fact, the illustration was drawn by a Strasbourg

artist who never saw a native American; he based his drawing on

Renaissance concepts of the ideal human body.

11.

Martin

Waldseemüller, 1470-1521?

Cosmographiae introductio cum quibusdam geometriae ac astronomiae

principiis ad eam rem necessariis . . .

Saint-Dié:

Gautier Lud, 1507.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V6 M15 1509 Vault

This is the book that gave the name "America" to the newly discovered

lands in the West.

In 1506, Martin Waldseemüller and

several other humanists were working together at the court of Duke

René, in the little town of Saint-Dié, in the

Vosges Mountains of northeastern France. The humanists and their patron

shared an interest in astronomy and cosmography. Together they were

compiling a world atlas based on Ptolemy's Geography.

The German humanist Matthias Ringmann joined the Saint-Dié group,

bringing his translation of Vespucci's second letter. In comparing

Vespucci's account to the works of Ptolemy, he discovered that the lands

Vespucci described related to a new world not mentioned by Ptolemy, a

world apparently lying under the Antarctic pole. Excited by this

discovery, the humanists decided to produce a world map to include the

lands not mentioned by Ptolemy.

Waldseemüller and Ringmann wrote this small tract on cosmography

to serve as an introduction to the world map as well as to their planned

atlas. It was entitled An introduction to cosmography with

several elements of geometry and astronomy required for this

science, and the four voyages of Amerigo Vespucci. In the text the

authors suggested that the new lands, which formed the fourth part of

the world, should be named "Amerigo" or "America" to honor Vespucci,

whom they believed had discovered them. The little volume was widely

distributed.

A few years later, Waldseemüller realized that these were the same lands

earlier discovered by Columbus on his third voyage. He removed the name

"America" in later editions, but by then it had become generally

accepted. Despite all the efforts by Columbus and the Spanish monarchs

to publicize Castile's discoveries and claims, the name of the Western

Hemisphere would forever belong to Vespucci, an Italian businessman who

had no role in its first exploration by Europeans.

The book is open to the Saint-Dié humanists' introduction to

Vespucci's letter, where the authors give their reason for the name

"America":

Now, really these [three] parts [Europe, Africa, and Asia]

were more widely traveled, and another fourth part was discovered by

Americus Vesputius (as will be seen in the following pages), for which

reason I do not see why anyone would reasonably object to calling it

(after the discoverer Americus, a man of wisdom and expertise)

"Amerige," that is, land of Americus, or "America," since both "Europa"

and "Asia" are names derived from women.

12.

Hernando Cortés,

1485-1547.

Praeclara Ferdinando Cortesii de noua maris oceani Hyspania

narratio . ..

Nuremberg: Friedrich Peypus,

1524.

Lilly Library call number:

F1230 .C8 1524 Vault

By 1515, Spaniards had established twenty-seven cities and towns on the

four major Caribbean Islands—Española, Cuba,

Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. They had tried to establish cities and towns

on the mainland, the east coast of which they had explored and mapped

from Brazil to southern Georgia. Yet every Spanish colony on the

mainland had been destroyed by epidemic, crop failure, or native attack.

If they were going to secure sovereignty over the mainland, they would

have to conquer the native rulers first. This means of effective

occupation became the norm in the European colonization of the Americas.

Hernando Cortés led the first successful conquest of a native

ruler on the American mainland. Leading an expedition of about four

hundred men, Cortés sailed from Cuba in 1518 and won the support of

dozens of Indian city-states that had been conquered by Moctezuma's

expanding Mexica (Aztec) empire. With the assistance of about 100,000

native warriors from these allies he had conquered Moctezuma's capital

city of Tenochtitlán (Mexico City) by 1522.

Cortés described his expedition's progress, defeats, and

victories in five long letters he sent to the new ruler of Spain,

Charles V. In his second letter, Cortés described the allied

army's march from the coast at Veracruz to the valley of Mexico,

Moctezuma's capitulation to the invading forces, and the allies'

occupation of the capital. The Spaniards, who considered cities to be

the mark of a civilized society, marveled at the sophistication and

monumentality of Mexico City. They also expressed horror and disgust at

some of the Mexica religious rites.

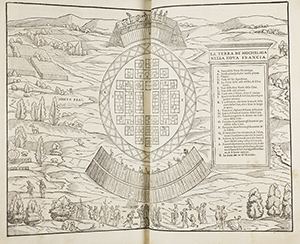

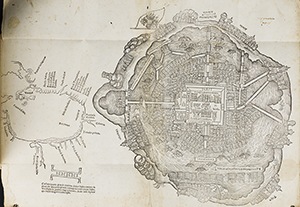

The book is open to a map of Mexico City that accompanied Cortés's

second letter to Charles V. This is the first map of any American city.

This map is also the first to contain the designation "La Florida." It

lies to the northeast of the Yucatán, Cuba, and the Panuco

River.

Within the city, we can see its canals and massive architecture,

including pyramids and ball court. We can also see the skull rack, where

the Aztecs displayed the heads of captives and hostages who had been

sacrificed in the temple of the main pyramid. In this Latin translation,

the skull rack is labeled capita sacrificatorum.

13.

Escrituras casa en la calle real, Mexico.

1527, May 9-1648, July 13.

Lilly Library:

Latin America mss. Mexico

Although the Mexica succeeded in defeating and expelling the Spaniards

and their allies from Tenochtitlán in 1520, Cortés

retreated to the allied city of Tlascala and formed a new army with

reinforcements from another Spanish expedition. This much larger force

definitively conquered the Mexica's new lord Cuauhtemoc, who had led a

heroic resistance.

Immediately after the conquest, the Spaniards occupied the land and

buildings. In order to distribute the property according to Castilian

law, Cortés carried out a survey of all the property in the

city. He took the property, tribute, and other income that had belonged

to the ruling dynasty and turned it over to the Spanish monarchy. The

properties and income of the native temples became the property of the

church. Private houses and lots in the city became the booty of the

conquerors.

This manuscript is a bill of sale for a house and its lot in Mexico City.

Cortés had given the lot to one of the conquerors, Juan

Ximénez, in 1524, and on

May 9, 1527, Ximénez sold it to

another Spaniard, Ruy Pérez, for 100.5 pesos of gold.

The manuscript is open to the 1527 bill of

sale containing the property description:

A lot that I have and own in this city [of Temistitan],

which is adjoined on one side by the property of Alonso Galeote, on the

front by the street, and in back by the property of Hernando de Xerez.

The sale included the lot, buildings, and some building stone.

14.

Antonio Pigafetta,

ca. 1480/91-ca. 1534,

and Transylvanus Maximilianus.

II viaggio fatto da gli Spaniuoli a torno a' l mondo . . .

Venice: Lucantonio Giunta,

1536.

Lilly Library call number:

G420.M2 M4 1536 Vault

In 1519, an Italian merchant from Vicenza, Antonio Pigafetta, booked

passage on a fateful voyage departing from the Spanish port of Sanlúcar

de Barrameda, bound for Asia. Portuguese fleets had been traveling

around Africa to Asia for ten years, but this expedition was different;

the Portuguese captain of this fleet of five ships, Ferdinand Magellan,

was commissioned by Spain to find a route through or around South

America in order to cross the Pacific and reach Asia.

Spaniards had no illusions that this would be an easy voyage. In 1515,

Castile had sent an expedition with this same objective under the

command of the royal pilot Juan Díaz de Solís. The Solís expedition,

after carefully exploring the coast of South America from Brazil to

Argentina, entered the Río de la Plata, where Solís was killed by

natives, and the expedition fell apart. Where Solís had failed, Magellan

succeeded, though he too was killed by natives, in the Philippines,

before completing his voyage

At the end, a Spanish seaman named Juan Sebastián de Elcano

brought the fleet back from Asia. In the Spice Islands they sold the

leaking Concepción to buy a cargo of cloves, but Trinidad's

captain and crew chose to go back across the Pacific rather than

continue west. Elcano navigated the lone surviving ship Victoria around

Africa, and arrived home in September 1522, three years after the

expedition had departed. Victoria's cargo of cloves fetched such a high

price on the market that it paid for all the expedition's expenses and

turned a handsome profit for the expedition's stockholders.

The news of this first circumnavigation of the globe spread rapidly.

Hernando Cortés heard it the same year from the captain of a Spanish

colonizing expedition he ran into on the coast of Honduras; he

immediately wrote a note of congratulations to Emperor Charles V. Yet

for all the significance of this, Spain's first voyage to the Spice

Islands, we would know very little were it not for the Italian

passenger. Pigafetta wrote an account of the voyage in which he

chronicled the terrors of the violent passage through the Straits of

Magellan, the horrors of starvation and lack of drinking water during

the Pacific crossing, and the many intrigues and betrayals once the

fleet reached Asia.

This is the first Italian translation of Pigafetta's narrative. The book

is open to the final pages, which give a brief Brazilian vocabulary.

15.

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, 1500-1558.

Letter to Antonio de Mendoza.

1537, Feb 16.

Lilly Library:

Latin American mss. Mexico

As Spanish explorers penetrated the interior of Mexico and moved farther

north, the monarchy delegated to the viceroy of New Spain the power to

draw up contracts, or capitulations, between the crown and the explorer.

The first viceroy of New Spain, Antonio de Mendoza, arrived at his post

in Mexico City in 1535 and immediately began regularizing the government

and extending Spain's effective occupation of the North American

continent.

A couple of years later, Emperor Charles V sent him this letter

recommending Francisco Vásquez Coronado

(1510-1554). The king reminded

his viceroy that Coronado's father and brother had both served the

Spanish monarchy and suggested that Coronado be given important

assignments that would benefit the monarchy.

Clearly, the king was approving an appointment that Mendoza had already

suggested. In 1539, the viceroy commissioned Coronado as commander of an

expedition that was being assembled to explore the present southwest

United States. The Coronado expedition, comprising 336 Spaniards,

hundreds of Indian guides and bearers, and more than 1,500 horses,

mules, and livestock, began moving north from Culiacán on April

22, 1540.

During the next two years, the Coronado expedition explored Arizona, New

Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. Without being aware of it, the

expedition at one time was within seven hundred miles of the De Soto

expedition, which was exploring westward from Florida and Georgia to the

Mississippi. The Coronado expedition began its return

march to Mexico City in early April 1542, after Coronado had been

seriously injured in a riding accident. For Europeans, his explorations

transformed North America from an imaginary island into another new

continent for colonization.

16.

Leyes y ordenanças nueuame[n]te hechas por su magestad, pa[ra]

la gouernacion de las Indias y buen tratamiento y conseruacion de

los Indios: que se han de guardar en el consejo y audie[n]cias

reales q[ue] en ellas residen: y por todos los otros gouernadores

juezes y personas particulares dellas.

Alcalá de Henares: Juan de

Brocar, 1543.

Lilly Library call number:

F1411 .S73 L68 1543 Mendel

The laws that had traditionally governed Spain soon proved to be

inadequate to deal with the many new situations that arose as Spaniards

and native Americans struggled to live together. On the recommendation

of many colonists and royal officials, Emperor Charles V issued new laws

for the Americas. These laws were designed to improve the administration

of the colonies and provide a more effective judicial system.

The most controversial parts of the New Laws attempted to improve the

situation of the native Americans and eliminate colonists' control over

Indian labor. Colonists who had the most to lose objected vehemently, so

the viceroys implemented the laws gradually and piecemeal, compromising

in some situations and discarding ordinances in others. By about 1570,

three-quarters of the grants of Indian labor to private individuals had

been converted to taxes and service paid to the royal treasury. By the

end of the century, the old system of Indian labor was effectively

ended. Indians in most of Spanish America had become, like Spaniards

themselves, taxpayers to the royal government rather than forced

laborers.

17.

Juan

Ginés de Sepúlveda,

1490-1573.

Apologia Ioannis Genesii Sepulvedae pro libro de iustis belli

causis ad amplissimum, & doctissimum praesulem.

Rome: Valerio and Luigi

Dorici, 1550

Lilly Library call number:

F1411 .S47 Vault

From the beginning of the American enterprise, many Spaniards were

troubled by the moral and legal questions posed in the Americas.

Particularly vexing was the question of whether native Americans should

be allowed to continue their own life style or should be integrated into

the mores of Europeans.

Dr. Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, eminent humanist at the

University of Salamanca and translator of Aristotle, used the reasoning

of the ancient Greek philosopher to address this question. Employing

Aristotle's theory of natural slavery, Sepúlveda argued that the

natives' political inferiority, idolatries, and other sins were in their

very nature. They were not capable of change by their own volition or by

the example of Europeans. Only by war and consequent enslavement could

barbarous customs such as idolatry, cannibalism, and human sacrifice be

ended.

Sepúlveda also based his argument on the papal decree of 1493

that divided the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of exploration. Because

the pope had granted sovereignty over the Western

Hemisphere to Spain and charged the Spanish monarchy with responsibility

for converting the natives to Christianity, Spain should end these

practices abhorrent to Christians. Conquest of the Indians was

necessary, and therefore constituted a just war.

The book is open to Sepúlveda's discussion of the papal decree

and its logical consequence, war against barbarous Indian practices in

the Americas.

18.

Bartolomé de Las Casas, 1474-1566.

Tratado co[m]probatorio del Imperio soberano y principado

universal que los reyes de Castilla y León tienen sobre las

Indias. Seville:

Sebastián Trugillo, 1553.

Lilly Library call number:

F1411 .C28 Vault

The greatest opponent of Sepúlveda's conclusions, though not

of his reasoning, was Bartolomé de Las Casas, a Dominican

friar who had lived in the Indies, where he had inherited from his

father a grant of Indian labor on the island of Cuba. Horrified by the

consequences of the Indian labor grants, Las Casas devoted most of his

life to saving the Indians from the Europeans. In order to develop his

power of argument, he studied logic and philosophy at the University of

Salamanca.

Vehemently opposed to forced conversion, and therefore to conquest, Las

Casas argued that the Indians were in an early stage of development,

just as Europeans had been millennia before. They were capable of

acquiring European culture by example and therefore should live in

settled communities in the presence of priests and other good Europeans.

In 1550 Emperor Charles V summoned jurists, including Sepúlveda and Las

Casas to debate the issue. The famous debate before the emperor in

Valladolid produced no resolution. It is important to remember that Las

Casas and Sepúlveda both wanted to achieve the same

objective—conversion of the Indians to Christianity and the

end of their barbarous practices—and that they both used

Aristotelian logic to make their arguments.

The volume contains a collection of nine tracts by Las Casas. Here, it is

open to the first tract, where, in order to lay the basis for the

reforms he was demanding, Las Casas presents proofs that Spain has

legitimate sovereignty by virtue of the papal decree of 1493.

19.

Philip II, King of Spain,

1527-1598.

Grant of liberty to the town of Tlascala.

1556, August 24.

Lilly Library:

Latin American mss. Mexico

As the conquest generation aged and passed away, the lines between Indian

and Spaniard became blurred. Spaniards and Indians married; their

children were legally considered Spaniards, regardless of race or

language. Spanish colonists and American Indians became bilingual, using

both Spanish and the dominant local Indian language. Government policy

integrated Indian communities into the Spanish political system.

Some Indian communities were particularly eager to obtain the benefits of

full political integration. Hernando Cortés had been able to conquer the

Aztec capital largely because he persuaded dozens of Indian towns to

become his allies. Among the first and most important of these allies

was the Indian town of Tlascala. After the conquest, the Spanish

government tended to treat all Indian towns alike, despite their varying

roles in the conquest. This, of course, offended and worried the

Tlascalans. They sued, protesting that their original agreement had been

violated.

In 1556, King Philip II granted this charter of liberty to the town of

Tlascala. He assured the Tlascalans that they would forever enjoy all

the freedoms, tax exemptions, and privileges of a Spanish town.

The document is open to the text issued by the royal chancery and its

translator, with matching texts in Spanish and the Aztec language,

Nahuatl.

20.

Títulos de las casas que compró

Catalina Vázquez en el barrio de Tomatlán.

1562, Oct 4-1597, Nov. 18.

Lilly Library:

Latin American mss. Mexico

Both Spaniards and Indians made full use of the judicial system to press

their claims and ask for redress of grievances. In property disputes,

the litigants submitted testimony and legal documents in both languages

and also in the pictorial tradition of Nahuatl manuscripts.

This bill of sale is written in both Spanish and Nahuatl, and the property is

sketched showing the Indian owners in residence. The owner of one house

is don Diego de San Francisco and the other is doña María Francisca.

21.

Juana de Austria 1535-1573.

V. Md. aprueba el assiento que se ha tomado con don

Francisco de Mendoça.

1558, Dec 10.

Lilly Library:

Latin American mss. Mexico

The original intention of Fernando and Isabel had been to find a western

route to Asia and its spices. In the mid-sixteenth century, the Spanish

monarchs were still trying to enter the spice trade. In Francisco de

Mendoza they thought they had found the ideal spice producer. Mendoza

had gone to New Spain (modern Mexico) as a teenager with his father,

Antonio de Mendoza, the first viceroy. For twenty years, Francisco

assisted his father and engaged in business.

After his father's death, Francisco returned to Spain. He was looking for

a profitable investment for the silver he had brought back, both for

himself and for other colonists who had made their fortunes in the

Americas. The American investors thought that Francisco would be the

ideal investment manager in Spain; his relatives were among the most

powerful nobles at court.

In this royal concession, Princess Juana

granted Francisco a monopoly on the planting and marketing of Asian

spices—Chinese ginger and sandalwood—in New Spain.

In return for land, a sufficient number of Indian laborers, and start-

up tax exemptions, Francisco agreed to pay the monarchy

one-half of all the profits on his spice sales.

All of this came to nothing, however. A few weeks later, the princess

commissioned Francisco to inspect all the mines in Spain and recommend

which ones the monarchy should develop. Once Francisco had completed

this assignment, the king appointed him director of the royal mines, and

he spent the rest of his life in the royal service in Spain. He never

went back to New Spain. Other Spaniards took up the project, however,

and a century later ginger had become one of the leading cash crops of

the town of Coamo in Puerto Rico.

The last page of the manuscript displays the signatures and rubrics of

all the officials who signed off on this contract, including the

princess and the king.

22.

Richard

Hakluyt, 1552-1616. The principall navigations, voiages and

discoveries of the English nation, made by sea or ouer land . . . .

London: George Bishop and Ralph

Newberie, 1589.

Lilly Library call number:

G240 .H14 1589 Vault

While the Spanish monarchy sponsored dozens of expeditions of exploration

by sea and land and Spanish colonists founded and settled more than a

hundred cities and towns in the Americas, the English made no effort to

establish their presence in the New World. English fishing fleets, along

with ships from Portugal, Spain, France, and Scandinavia, made seasonal

trips to the fishing banks of North America, drying and salting their

catch onshore and then carrying their cargo back to Europe in time for

the Lenten season. The French king Francis I made several unsuccessful

attempts to claim and settle parts of North America and Brazil, but in

England neither the queen nor Parliament regarded the Americas as an

important objective of royal policy; they were busy conquering and

colonizing Ireland.

One Englishman and his son, both named Richard Hakluyt, had very

different ideas. They had the mentality of the space race in modern

times and began publicizing their views with Parliament and the royal

court. They convinced Sir Humphrey Gilbert and, after Sir Humphrey's

death, his half-brother Sir Walter Raleigh that England should challenge

Spanish sovereignty over North America by establishing effective

occupation. Sir Walter organized and financed a colonizing voyage, which

established a short-lived settlement on Roanoke Island, Virginia.

Despite the failure of the Roanoke venture, Hakluyt remained convinced

that the English should colonize North America. In order to publicize

this idea and bring pressure on the royal government and Parliament,

Hakluyt began publishing narratives of early voyages to North America.

For the foreign voyages, he commissioned translations into English, but

his principal objective was to use the early English voyages as a legal

basis for English sovereignty in North America. Hakluyt's efforts bore

fruit in the seventeenth century, when England was devastated by

religious persecution and civil war. Hundreds of thousands of English

people fleeing the turmoil and dangers of their own country turned to

Hakluyt's narratives and, believing his rosy picture of America,

emigrated to Virginia and New England.

Publication of these narratives of exploration in English translation

continues to the present day, under the title Hakluyt's Voyages.

23.

Francisco Fernández de la

Cueva Enríquez,

d. 1733, et. al.

Documents concerning the sending of twelve Indian families to

Florida.

1703, Sept. 11-1704, Apr. 5.

Lilly Library:

Latin America mss. Mexico

With English settlers moving into Virginia and Georgia and making

incursions into Florida, the Spanish government wanted to encourage

Spanish colonies in North America. Those in Florida were particularly

important because they secured the coast along the major route for the

return voyage of the annual silver fleets.

The government decided to use a method that had developed in other

frontier colonizations. Traditionally, Spaniards and Indians from

already-colonized regions went to settle the northern frontier. The

colonists who settled New Mexico in the late sixteenth century, for

example, came mostly from the silver mining towns of northern Mexico.

This time, the viceroy of New Spain, the duke of Albuquerque, found

Indians from New Spain who were willing to emigrate to Florida. The

manuscript is open to the first page of the viceroy's decree authorizing

twelve Tlascalan families to colonize Florida. The signature reads

"Duque de Albuquerque."

24.

Ulrich von Hutten, 1488-1523. Of the wood called guaiacum, that

healeth the frenche pockes, and also helpeth the goute in the feete,

the stone, palsey, lepre, dropsy, fallynge euyll, and other diseses.

Made in Latyn by Ulrich Hutten, knyght, and translated in to Englysh

by Thomas Paynel. London:

Thomas Berthelet, 1540.

Lilly Library call number:

R520.6 .H9 1540 Vault

With the Atlantic transformed from obstacle to conduit, people, plants,

and animals moved back and forth between Europe and America for the

first time. Species that had existed only on one side of the Atlantic

now became common on both sides, a process we now call the Columbian

Exchange.

One of the negative effects of the Columbian Exchange devastated native

American cultures; disease-bearing microorganisms from Europe infected

hundreds of thousands of American Indians. Diseases such as measles,

typhus, and small pox had not existed in the Americas, and when the

indigenous population was first exposed, they all got sick at once. When

most of a community is seriously ill at the same time, there is no one

to care for the sick. People who might have survived with adequate

drinking water, food, and clean conditions died of dehydration and

secondary infections.

Only one disease, syphilis, traveled in the opposite direction. There now

seems little doubt that syphilis was in the Americas prior to 1492 and

came to Europe on Columbus's return in 1493. Most Europeans called it

the "French disease," because the first cases appeared in the French

army that invaded Italy in 1494.

By 1500, syphilis had become an epidemic, spreading rapidly throughout

Europe in a pattern characteristic of a new venereal disease in a

population having no prior immunity.

Diagnoses and treatments were suggested by many physicians, including the

Italian Girolamo Fracastoro and the Spaniard Pedro Mexía (who called it

the "Indies disease"). The afflicted desperately sought any concoction

that might give relief from the painful and disfiguring symptoms, even

when the treatment was as bad as the disease. A German knight who was

infected with the disease, Ulrich von Hutten, published this treatise

advocating the use of guaiacum, the extract of an American wood. The

book was immediately popular throughout Europe and appeared in English

translation in 1540.

25.

Nicolás Monardes, ca. 1512-1588.

Primera y segunda y tercera partes de la historia medicinal de

las cosas que se traen de nuestras Indias Occidentales que sirven en

medicina.

Seville

Alonso Escrivano, 1574.

Lilly Library call number:

RS169 .M5 1574 Vault

26.

Nicolás Monardes, ca. 1512-1588.

De simplicibus medicamentis ex occidentali India delatis, quorum

in medicina usus est . . .

Antwerp: Christophe Plantin,

1574.

Lilly Library call number:

RS169 .M56 1574

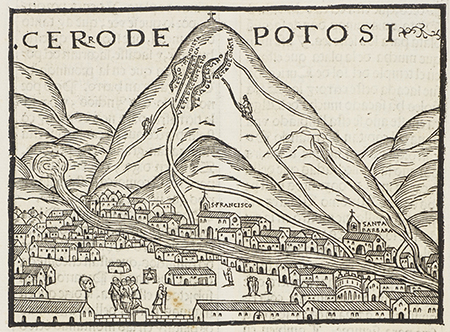

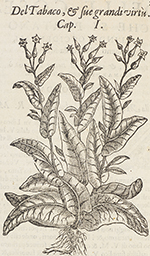

This Antwerp edition of Monardes's book on the medicinal uses of American

plants is open to his discussion of tobacco as a medicine.

27.

Nicolás Monardes, ca. 1512-1588.

Delle cose che vengono portate dall'Indie occidentali pertinenti

al'uso della medicina.

Venice: Giordan Ziletti,

1582.

Lilly Library call number:

RS169 .M55 1582

28.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1478-1557.

La historia general de las Indias.

Seville: Juan Cromberger,

1535.

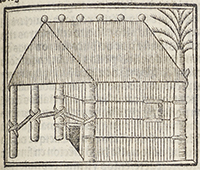

In the first century of colonization, Europeans who stayed at home wanted

to know the ways that native American societies were different from

their own. Consequently, colonial writers filled their books with

descriptions and illustrations of every aspect of native America that

was unknown in Europe. When colonial writers did not describe some

aspect of Indian society, we can safely assume that it was considered

too similar to Europe to warrant mention.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo spent most of his life in the

Americas as a royal inspector of mines and as commander of the fortress

at Santo Domingo. Fascinated by the local customs and the exploits of

the Spanish conquerors, Oviedo recorded his observations of native

customs, artifacts, flora, fauna, and language, and he interviewed

participants in Spanish expeditions to the American mainlands.

An incurable reviser of his own work, even after publication, he

composed, expanded, and rewrote his books on board ship during his

thirteen transatlantic voyages. To him we owe much of what we know of

Indian words, customs, and skills.

In his second book, On the general and natural history of the Indies,

Oviedo described how the islanders made their dugout canoes, even though

they had no metal tools to work with:

On this island of Española and in all other coasts and rivers of the

Indies that Christians have seen up to now, there is one type of

boat, which the Indians call 'canoe.' With these they navigate the

great rivers as well as the oceans for purposes of war and raid, for

conducting commerce between one island and another, or for fishing

and other purposes. Without these canoes, we Christians who live

here could not benefit from our property on the coasts and

riverbanks.

Each canoe is a single branch or tree trunk, which the Indians hollow

with blows of stone-headed axes, like the one illustrated here. With

these they cut or scrape the wood to hollow it. Then they burn what

has been beaten and cut little by little. When the fire goes out,

they again cut and beat it, alternating these two processes until

the boat is formed to the limits of the width and length of the tree

trunk.

I've seen them large enough to carry forty-five men, wide enough to

hold a wine cask easily between the Carib Indian archers. The Caribs

use them as large as I have mentioned and call them pirogues,

navigating with cotton sails and by oar, as well as with their

paddles, as they call their oars. Sometimes they paddle standing, at

times sitting, and kneeling when they feel like it.

Some of these canoes are so small that they hold no more than two or

three Indians, others hold six, others ten, and on up. But no matter

what size, they are very light and dangerous, for they overturn

frequently. But they don't sink even when they are immersed. And

because these Indians are great swimmers, they turn them upright and

smartly empty them .... They are safer than our ships in case of

capsizing. Even though ours capsize less often because they are more

flexible and buoyant, once they are immersed they sink to the

bottom.

29.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1478-1557.

Coronica de las Indias. Salamanca:

Juan de Junta, 1547.

Lilly Library call number:

E141 .O89 1547 Vault

30.

Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, 1478-1557.

L'histoire naturelle et generalle des Indes, isles, et terre

ferme de la grand mer oceane. Paris:

Michel de Vascosan, 1555.

Lilly Library call number:

E141 .O893 1555

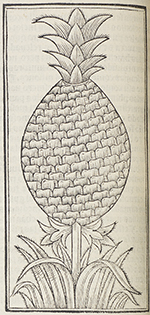

Oviedo was fascinated by the techniques American Indians had developed

for familiar tasks, such as preparing food, building houses, and

manufacturing tools and equipment. Here he illustrates the Indian method

of starting a fire without the flint and steel that Europeans required.

The native Americans rotated a stick poised on a piece of wood by

rubbing the stick between their hands to create heat.

31.

Denis le Chartreux.

Este es un compendio breue que tracta d'la manera de como se

han de hazer las processiones. Mexico

City: Juan Cromberger, 1544.

Lilly Library call number:

BX2324 .M6 D39 Vault

In 1539, the first printing press arrived in the Americas. It was

established in Mexico City as a branch of the Seville press owned by the

Cromberger family. Juan Cromberger in Mexico followed the same policies

he had learned in the family firm in Seville. In Europe, printing had

been a business from the beginning. Most printers were motivated by

profit and they tended to reproduce those texts that had already been

most in demand before the advent of printing.

Denis the Carthusian's little book on how to lead a Christian life had

been a Latin classic for two centuries when the new bishop of Mexico,

Juan de Zumárraga, commissioned this printing of Denis's

section on processions, in Spanish translation.

Clearly, the good bishop thought that Spanish colonists in America were

behaving no better than their medieval predecessors in Europe. The

section that he commissioned from Cromberger points out the behaviors

that are not suitable for holy processions: foolishness, pompous attire,

drinks inappropriate to the time and place, and above all buffoonery and

other lewd acts that provoke carnal sins.

32.

Francisco López de Gómara, 1510-1560?.

La istoria de las Indias y conquista de Mexico.

Saragossa: Agustín

Millán, 1552.

Lilly Library call number:

E141 .G5 1552 Mendel Vault

The secretary of Hernando Cortés, Francisco López

de Gómara, never saw America, yet he made excellent use of

reports and descriptions from members of the Cortés expedition. Gómara

devotes three chapters to Aztec women, focusing on practices that surely

would arouse the curiosity of Europeans; how women are buried, the

practice of polygamy, and marriage rites.

The book is open to a description of the Aztec writing and number systems

and the names of the months and days in the Aztec calendar.

33.

Pedro de Cieza de León, 1518-1560. Parte

primera de la chronica del Peru.

Seville: Martin de

Montesdoca, 1553.

Lilly Library call number:

F3442 .C29 Mendel Vault

34.

Hans Staden. Warhaftig Historia un Beschreibung eyner

Landtschafft der Wilden.

Marburg: Andreas Kolbe, 1557.

Lilly Library call number:

F2528 .S74 Vault

35.

Domingo de

Santo Tomás, 1499-1570. Grammatica, ò

arte de la lengua general de los indios de los reynos del Peru.

Valladolid: Francisco

Fernández de Códova, 1560.

Lilly Library call number:

PM6303 .D6 1560 Vault

36.

Doctrina Christiana y catecismo para instruccion de los

indios. Lima: Antonio

Ricardo, 1584.

Lilly Library call number:

PM6308.1 .D63 Vault

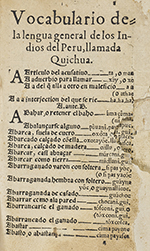

In contrast to the earlier Cromberger book in Mexico City, which was aimed at

laymen, this little book was intended as a manual for priests. The Spanish

priests in Peru already knew how to speak the native languages. In 1583,

they came from all over Peru, meeting in the Spanish capital, Ciudad de los

Reyes [Lima]. They translated the Catholic catechism into the two principal

native languages of Peru, Kechua, and Aymara, and commissioned this printing

from the press of Antonio Ricardo.

The catechism had been invented by Martin Luther, but Catholics soon compiled

their own. In Europe, children were required to memorize the fundamentals of

the Christian faith, in the form of prayers, the creed, and

question-and-answer sequences. The book is open to the first prayers that

every Catholic child learned, the "Lord's Prayer" and "Hail Mary." Here the

prayers in Spanish are followed by their translations into Kechua in the

left column and Aymara in the right column.

37.

Giovanni Battista

Ramusio, 1485-1557.

Terzo volume delle navigationi et viaggi.

Venice: Giunti, 1565.

Lilly Library call number:

G159 .R2 v. 3 1565

38.

Jean de Léry,

1534-1611.

Historia navigationis in Brasiliam quae et America dicitur.

Geneva: Heirs of Eustache

Vignon, 1594.

Lilly Library call number:

F2511 .L66 1594

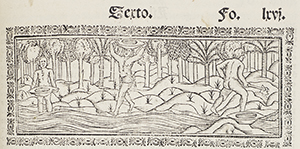

Jean de Léry recorded the history of an attempted French

settlement in Brazil in the mid-sixteenth century. The settlement failed

largely because of conflict among the colonists and hostility of the native

Americans. Léry found much to comment on in the exotic flora and fauna. He

provided careful drawings of Indian customs and regalia, and the publisher's

woodblock cutter transformed the Indians into classic beauties in the poses

of Greek gods. Here, he illustrates Indians dancing in feather headdress,

using a gourd shaker, with a monkey in the foreground and a parrot in the

background. On the facing page, Léry provides an example of an

Indian chant.

Discovering the Earth's Surface

Maps and Navigation

Europeans from the most ancient times had known that the world was a sphere, but none had ever imagined that a continent separated

Asia from Europe. The Columbian voyages, especially the third voyage that explored the coast of Venezuela

in 1498, revolutionized

European concepts of geography and provided new data for the science of navigation.

As they acquired new information by exploring the Americas, pilots, map-makers, and scientists over the next century were

able to

improve estimates of the earth's circumference, determine the true extent of the earth's land masses and

oceans, and establish the

longitude and latitude of most ports and cities all over the globe.

Changes did not come easily. Instruments were rudimentary and timepieces unreliable. Navigators who achieved splendid practical

results by dead reckoning also made and recorded celestial observations that were wildly inaccurate.

The Portuguese king

insisted that his captains use an erroneous method of determining longitude. Many publishers did not

bother to update maps

when they issued new editions.

Columbus and other captains depended on experienced pilots who conducted their Spanish voyages to the Americas by dead

reckoning.

Working from route charts, they took advantage of wind and sea currents in the Atlantic and drew on their

years of experience at

sea to calculate fairly accurately the north-south distance (latitude) traveled. Longitude was more difficult

to estimate.

Nevertheless, by the year 1500, dozens of Spanish voyages had traveled safely to and from the Western Hemisphere, piloted by men

like Juan Aguado, Columbus and his brother Bartolomé Colón, Juan de La Cosa, Alonso de Hojeda, Andrés

de Morales,

Peralonso Niño, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, Bartolomé Roldán, Alonso de Torres, and Juan de Umbría.

These were just some of the better-known pilots and navigators. There were many, many more.

In the beginning of transatlantic navigation, few records were made public. Ship's logs were not kept until the sixteenth

century—

Columbus's diary from his first voyage being the great exception. A few Portuguese pilots kept records

that they turned over to

their king for inclusion in the royal cosmographical charts and tables. But these charts were state secrets

not shared with other

nations. As a result, we know very little of how any one of these voyages was navigated.

Despite this policy of secrecy, the published works displayed here indicate great changes in methods of navigation. The first

changes made celestial navigation practical for seafaring. For centuries, land travelers in desert

regions had observed the

stars. Like seafarers, desert travelers had no landmarks by which to orient themselves, and a sophisticated

science of celestial

navigation had been developed by Arab scientists. Celestial observations were extremely difficult at

sea, however, and the

Atlantic offered no handy islands along the way to take

steady, accurate readings. To overcome these difficulties, Spanish and Portuguese pilots and mathematicians

invented new instruments

for observations, improved old ones, added new data from the Southern and Western Hemispheres, and compiled

tables of altitude,

longitude, and latitude. Increasingly, seamen made use of celestial navigation in transatlantic voyages,

although dead reckoning

remained essential until the modern development of accurate and reliable timepieces.

In order to define their position on the earth's surface in circular measure, seamen needed a common set of coordinates for

longitude and latitude. The method for measuring latitude from the altitude of the sun or a circumpolar

star at meridian

altitude was developed during the fifteenth century.

Longitude, however, proved much more difficult to calculate. Since ancient times, scientists understood that the earth's

rotation is synonymous with time. Longitude could be measured by timing an astronomical event, such

as an eclipse or the

conjunction of planets, that could be seen simultaneously by observers in different places. By extrapolating

from the time

difference, they could estimate the distance separating them. Arab mathematicians in Spain, in fact,

had drawn up tables

showing the positions of a heavenly body at regular intervals in time when observed from Toledo, so

that they could be used in

other places.

The problem was that the timepieces of the day were not reliable enough to calculate time accurately. The rate of the earth's

rotation is such that one degree of longitude corresponds to four minutes of time. By the year 1500 the best mechanical clocks

were subject to an error of about ten minutes a day. Columbus tried to determine longitude by observation

of eclipses while at

anchor in the Caribbean in 1494 and 1504 using published tables.

He miscalculated the true longitude in 1494 by 22°30'; in 1504 by 38'.

With errors of this magnitude common, celestial navigation was not practical. The tables and instruments were not adequate

for

navigation or cartography. In Portuguese and Spanish Attempts to Measure Longitude in the 16th Century,

W. G. L. Randles notes that the Portuguese king ordered pilots to use an erroneous master chart of the

route to India on

which longitudes had been determined by lunar and solar eclipses. The result had been shipwrecks. Portuguese

pilots

therefore had their charts made secretly in Spain, using traditional methods.

39.

Laurentius Corvinus,

1465?-1527.

Cosmographia dans manuductionem in tabulas

Ptholomaei . . . Basel: Nikolaus

Kessler, 1496.

Lilly Library call number:

G87 .P97 C8 1496 Vault

The Geography of Ptolemy, originally written in the second century, was

not known during most of the Middle Ages. A Byzantine monk, Maximus

Planudes, (ca. 1260-1310) discovered a copy of

the Geography in 1295. It had no maps, so he reconstructed

them from the coordinates in the text. In 1405, the Florentine humanist Jacobus Angelus

made the first Latin translation and changed the title to

Cosmography.

Ptolemy's organization of his work into eight books became the model for

all geographies for centuries after the Latin translation first

appeared. In Book 1, Ptolemy stated his objectives: to give coordinates

of places and geographical features and make recommendations for

creating a world map and regional maps. The remainder of the book gives

names and coordinates for all the oikumene (known world): Books 2 and 3

cover Europe; Book 4, Africa; Books 5 through 8, Asia and a summary.

Though the map (if it ever existed) did not survive, the text provided

tools essential for drawing one: a system of coordinates based on

longitude and latitude, instructions for making rigorous maps, and a

critical scientific attitude.

Laurentius Corvinus edited Ptolemy's Geography, collating

the Greek place names with Latin place names. Like all editors of the

Geography, he was tantalized by Ptolemy's list of

place names from ancient texts whose locations were not

known—the Terrae incognitae.

40.

Pomponius Mela,

fl. 43-50.

Cosmographia pomponii cum figuris.

Salamanca: 1498.

Lilly Library call number:

G87 .M48 1498 Vault

Despite the official policy of keeping navigational information secret,

scientific curiosity about the newly explored territory was so intense

that scholars managed to piece together reports from ship's officers and

integrate the information into new views of the earth.

The cosmographical treatise by the ancient writer Pomponius Mela was a

popular textbook for undergraduates at the University of Salamanca in

the late fifteenth century. This edition by Francisco

Núñez de la Yerva, professor of medicine at the

university, placed emphasis on teaching students the longitude and

latitude of Europe's large cities and ports. The didactic tone of the

edition is so intense that, on the title page, Núñez gives the

longitude and latitude of Salamanca, where the book was printed:

cuius loci elongatio ab occidenti. IX & ab

equinoctiali xlj. gradibus constat.

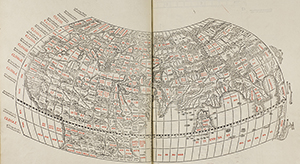

The book is open to the

famous first Spanish world map. The map is a graduated planisphere

showing longitude and latitude of the major ports and cities.

41.

Gregor

Reisch, d. 1525. Margarita

philosophica. Freiburg:

Johann Schott, 1503.

Lilly Library call number:

AE3 .R375 1503

Gregor Reisch published this compendium of information about all parts of

the world ten years after news of Columbus's first voyage was published

throughout Europe.

The world map included in Reisch's encyclopedia shows many Chinas

(Sinarum Regio, Sinarum Gangeticus, Sinus Persicus, Sinus Arabicus,

Sinus Hisperioris) and many Indies (India Indus, India Intra Gangem

Fluvium o Bragma, India Extra Gangem Fluvium). Reisch labels the areas

south of India as "Extra Gangem Fluvium" and north of Scithia [modern

Siberia] as lands of cannibals (Anthropophagis).

Reisch's world map does not show Columbus's Indies, but some scholars

believe that a legend at the bottom of the map may refer to the New

World: "Here is not land but sea, in which are many unknown islands,

according to Ptolemy."

42.

Jan Glogowczyk, 1445-1507.

Introductorium compendiosum in Tractatum Spere materialis

magistri Joannis de Sacrobusto . . . per magistrum Joannem

Glogoulensem . . . Crakow: 1506.

Lilly Library call number:

QB41. G56

This is the earliest printing of a small work that was to assume great

importance in the history of early nautical astronomy, De sphaera

mundi. It was written in the early thirteenth century by the

Englishman Johannes de Sacrobosco, or John of Holywood, probably as an

introduction to a more advanced course on astronomy and cosmology. It

became a standard text during the age of discovery.

The treatise is based largely on the work of the great Arab astronomer

Alfraganus (Al Farghani, d. 861) and presents the Ptolemaic system as

put forward in Alfraganus's Almagest. It gives proofs of

the sphericity of the earth; it defines astronomical and terrestrial

terms such as the ecliptic, equator, small and great circles, meridians,

astronomical coordinates, and the twelve signs of the zodiac; and it

explains various astronomical phenomena, such as eclipses.

It was Alfraganus whose calculation of the degree of the

meridian—56 ⅔ miles—so misled Columbus,

who failed to take into account the difference between the Arabic and

the Italian mile.

43.

Fracanzano

da Montalboddo.

Paesi nouamente retrouati. Et nouo

mondo da Alberico Vesputio Florentino intitulato.

Vincenza: H. and G. M. de Sancto

Ursio, 1507.

Lilly Library call number:

E101 .F8 1507 Vault

After his short sojourn in Portugal, Amerigo Vespucci returned

to Spain, became a Castilian citizen, and was appointed to the new post

of Pilot Major. The Pilot Major's job was to maintain and update the

master sailing chart for Castile, to certify pilots, and to inspect

nautical instruments for accuracy.

Vespucci's appointment to this office is something of a puzzle.

Christopher Columbus recommended Vespucci to Queen Isabel as an

experienced business agent and ship's chandler. Vespucci, as far as we

know, never piloted a ship. Long before he became Pilot Major in

August 1508, dozens of Spanish pilots had already

navigated successful voyages to and from the Americas. There were plenty

of competent pilots and navigators available to the crown of Castile.

King Fernando probably had mixed motives for appointing him; Vespucci

claimed to have solved the problem of determining longitude, and if the

king did not keep him happy in Castile, Vespucci might sell information

about Spanish explorations and sailing charts to the Portuguese.

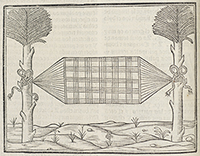

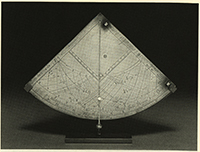

The book is open to an illustration for finding the altitude of Canopus

from two different positions. A first-magnitude star in the

constellation Carina, Canopus is the second brightest star in the

heavens.

44.

Martin Waldseemüller, 1470-1521?

Cosmographiae introductio com quibusdam geometriae ac

astronomiae principiis ad eam rem necessariis Insuper quattuor

Americi Vespucij nauigationes. Saint

Dié: Gautier Lud, 1507.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V6 W15 1507

Vault

With Columbus's voyage, mariners and scholars realized that Ptolemy's

text, and consequently the maps that had been drawn from it, contained

many gaps and errors. Ptolemy made the earth too small, treated the

Indian Ocean as closed, omitted sub-Saharan Africa, and was ignorant of

the Americas.

In their introduction to their planned world map, Waldseemüller

and his colleagues note the new continent, which they label America

because they mistakenly thought Amerigo Vespucci was the first to

describe it.

45.

Fracanzano

da Montalboddo.

Itinerarium Portugale[n]siu[m].

Milan: Joannes Angeles

Scinzeler, 1508.

Lilly Library call number:

E101 .F8 1508 Vault

In light of Portuguese explorations, Fracanzano published a map of Africa

in which the continent is accurately shaped and fully rounded, though

India and the rest of Asia remain vague and malformed.

46.

Claudius Ptolemaeus, fl.

127-151. Geographia. Rome:

Bernardino dei Vitali, 1508.

Lilly Library call number:

G1005 1508 Mendel Vault Flat

Early in the age of discovery, geographers found a way to correct

Ptolemy's errors without altering his text; they included updated tables

of longitude and latitude for many places not known to Ptolemy. For

example, Columbus's discoveries were added to the updated maps.

This reprinting of the 1507 edition has added a

world map by Johan Ruysch and an appendix by Marco of Benevento. The

list of place names with their latitudes and longitudes has grown to

thirty-six folios. Ruysch labeled American sites with the names Columbus

had given them.

47.

Martin Waldseemüller, 1470-1521?.

Cosmographie introductio.

Strasbourg: Johann

Grüninger, 1509.

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V6 W15 1509 Vault

The treatise on cosmography, which Martin Waldseemüller and

Matthias Ringmann wrote as an introduction to a planned world map, was

one of the earliest to incorporate information about the Western

Hemisphere. This little book became very popular and went

through several editions after it first appeared in Saint-Dié

in 1507. Two private citizens of the city of

Strasbourg published this new edition in 1509.

The earth is depicted in a cordiform (heart-shaped) image and marked in

degrees of latitude and longitude. The two parts of the recently

discovered American continents are separated by a strait, with the

western coast depicted for the first time but without delineation.

48.

Pietro Martire

d'Anghiera, 1435-1526.

. . .

Opera legatio babylonica occeani

decas poemata epigrammata. Seville:

Jacobus Croumberger, 1511.

Lilly Library call number:

E141 .A6 1511 Vault

49.

Claudius Ptolemaeus, fl.

127-151. Geographia.

Venice: Jacopo Pencio,

1511.

Lilly Library call number:

G1005 1511 Vault Flat

50.

Claudius Ptolemaeus, fl.

127-151. Geographia.

Strasbourg: Johann Schott,

1513.

Lilly Library call number:

G1005 1513 Mendel

Vault Flat

This edition was prepared by Martin Waldseemüller, Matthias

Ringmann (Philesius), Essler, and Uebelin. The text includes letters by

Pico della Mirandola, Essler, Uebelin, and Giraldi

(Ziraldus).

After completing the Cosmography, making wood-block gores

for a globe, and printing the sea chart and the world map, the humanists

at Saint-Dié resumed work on their long-delayed edition of

Ptolemy's atlas, to be entitled The geographical work of Claudius

Ptolemy, the man of Alexandria, a most erudite philosopher of

mathematical learning, closely reprinted by reproduction of the Greek

originals. In order to resolve disparities in place names and textual

content, the scholars turned to other manuscript and printed copies of

Ptolemy's atlas. The classical scholar Matthias Ringmann translated

place names and texts from Greek to Latin. Waldseemüller

designed the maps.

This is the book that gave the name America to the newly discovered lands

in the West. It includes Vespucci's letter to Piero Soderini, dated from

Lisbon on 4 September 1504, in which he

describes all four of the voyages he claimed to have made.

The book is open to one of forty-five double maps that Waldseemüller

designed for this edition.

51.

Martin Waldseemüller, 1470-1521?

Cosmographiae introductio cum quibusdam geometriae ac

astronomiae principiis ad eam dem necessariis.

Lyons: Jean de La Place,

1517-1518?

Lilly Library call number:

E125 .V6 W15 1517 Vault

During the ten years after their first publication in

Saint-Dié, Waldseemüller and his colleagues accumulated much

additional information about the Spanish and Portuguese voyages of

discovery. They revised some of their earlier misconceptions, realizing,

for example, that the lands discovered by Columbus and those reported by

Vespucci were the same.

On the South American continent, they deleted the name "America" and

inserted the labels "Brazil, land of parrots," and "all of this province

was discovered by mandate of the king of Castile." They also deleted the

strait between the two American mainlands.

Although only one set of the revised world map survives, the new

information was incorporated into the Cosmography's navigational

information in later editions. This 1517-1518 edition from Lyons is open to a chart for

calculating position.

52.

Pomponius Mela,

fl. 43-50.

De orbis situ libri tres . . .

Basel: Andreas Cratander,

1522.

Lilly Library call number:

G87 .M48 1522

Wishful thinking continued to dominate map making outside the Iberian

Peninsula. In this edition of Pomponius Mela's geography, the publisher

in Basel added a foldout map displaying a fictitious strait through the

Isthmus of Panama.

53.

Marco

Polo, 1254-1323.

Cosmographia breue introdutoria en

el libro de Marco Paulo. El libro d'l famoso Marco Paulo Veneciano

d'las cosas marauillosas que vido en las partes orientales. Conuiene

saber en las Indias. Armenia. Arabia. Persia & Tartaria. E

del poderio del gran Can y otros reyes. Con otro tratado de Micer

Pogio Florentino que trata de las mesmas tierras &

yslas. Seville: Juan

Varela, 1518.

Lilly Library call number:

G370 .P7 1518 Vault

Just as the ancient geographers Ptolemy and Pomponius Mela continued to

command respect, despite their obvious gaps and errors, the medieval

merchant explorer Marco Polo enjoyed a resurgence of popularity. Italian

humanists such as Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli and Poggio Bracciolini

attempted to draw geographical conclusions from Polo's descriptions of

Asia. This led to misconceptions—and momentous consequences.

Toscanelli, for example, read Marco Polo's description and interpreted it